Gender identity is defined as a person’s inner concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither. A person’s gender identity can be the same or different from their gender assigned at birth.

When a person is gender diverse, it may mean they do not conform to their society or culture’s expectations for males and females. Not all gender diverse people are transgender, which is a term that describes people who were assigned a gender that is different from how they identify. For example, a trans boy is a person assigned female at birth who identifies as a boy. Many young trans and gender diverse people experience distress related to the incongruence between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth which is called gender dysphoria.

- Gender diverse – someone who does not conform to their culture’s expectations for boys or girls.

- Transgender – describes an inner gender identity that is not in alignment with the gender assigned at birth.

What is gender diversity?

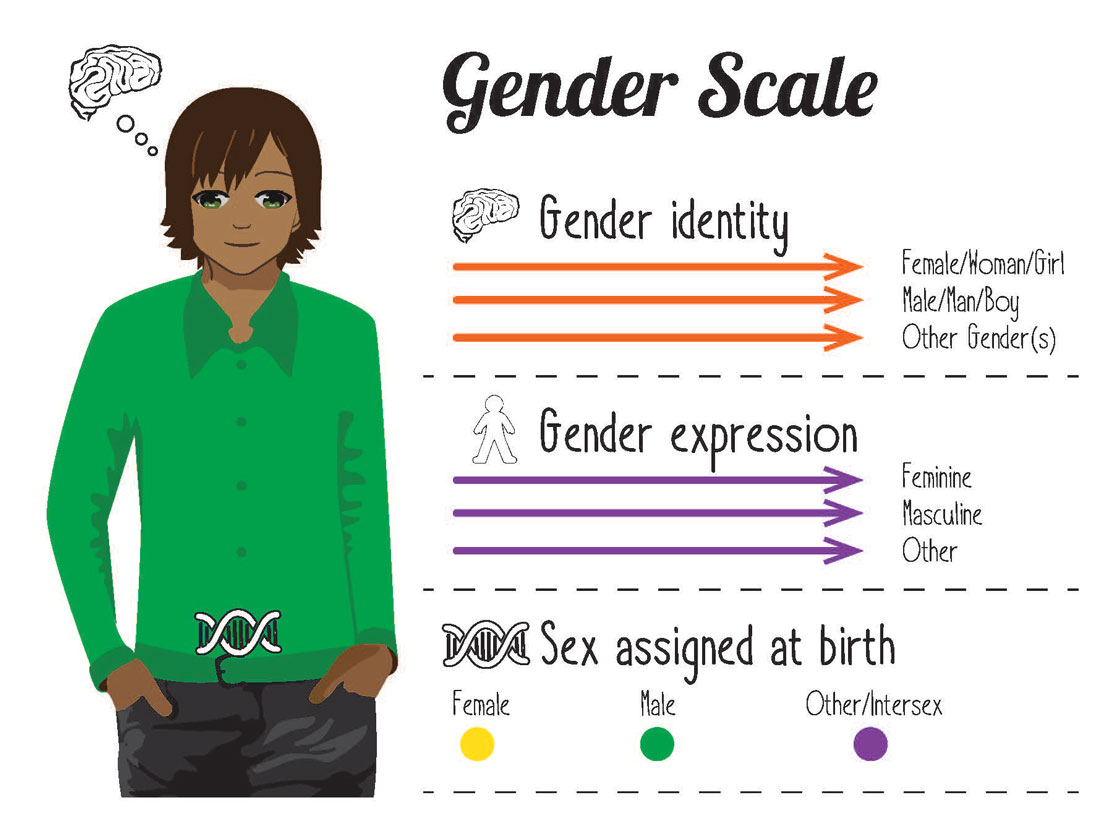

Understanding gender identity requires distinguishing between:

- Sex – the blend of physical characteristics including internal and external body formation, endocrine system/hormones and chromosomes.

- Gender expression – is shown via choice of our clothing, hair styles, gender roles and activities.

- Gender identity – internal sense of being male, female, a blend of both or neither.

Why seek help?

Most children will begin to self-identify their gender before they are five years old. This may show as preferences for types of toys, clothing and interests. Transgender or gender diverse children may express their gender differently to what is expected by their parents, either in childhood or teenage years. Experimenting with gender roles and rules in childhood is common and does not mean your child is transgender. The majority of children with gender non-conforming behaviour will identify with their assigned gender at birth around or after puberty.

Children or adolescents may become aware of their gender incongruence at different ages and will often become increasingly distressed. In children, this can create behavioural and emotional difficulties while in adolescence it increases the likelihood of anxiety, depression, self-harm or suicidal thoughts.

Gender dysphoria ranges from manageable to debilitating. Some young people and their families will be able to manage gender dysphoria with little or no help while others will be overwhelmed by the distress. For some young people, it can lead to problems with school performance/attendance, confidence and self-esteem, depression, anxiety, social isolation, self-harm and suicidal thoughts. Many young people’s experiences of bullying, family rejection, homelessness, harassment, discrimination or verbal and physical violence contribute to gender dysphoria.

Research shows that young people who have received specialist gender affirming medical intervention in childhood have mental health outcomes equal to their non-gender dysphoric peers in adulthood. Most importantly, the research in this area demonstrates a significant risk of harm in not providing treatment.

When should you seek help?

Speak to your general practitioner (GP) as soon as your child expresses discomfort or distress with their gender identity and ask for a referral to the Queensland Children’s Gender Service. It is best to do this sooner rather than later. No medical treatments are available before adolescence or the onset of puberty but support and information can be helpful to families of younger children with strong gender non-conforming behaviour or identification. For adolescents, the gender clinic can provide assessment, support and timely medical treatments that are effective in reducing gender dysphoria and supporting healthy social-emotional development.

Transgender young people who access specialist gender assessment and treatment grow up to have the same psychological wellbeing and quality of life indicators as other young people when:

- They receive specialist gender healthcare

- Families affirm their child’s gender expression and identity.

Treatment

There are effective interventions to reduce gender dysphoria that differ depending on a person’s stage of puberty, developmental stage and readiness relative to clinical guidelines. Care pathways are decided collaboratively between young person, parents/carers and the treating team.

Children before puberty

Assessment, information and support is provided for children and families who are distressed or concerned about a child’s gendered behaviour, preferences or stated identity. When a child’s interests are different from societal expectations, they can be noticed or even discriminated against by others. Understandably, parents may want to influence how a child plays or behaves in order to protect their child from stigma, but it is important to not make the child feel like they are doing something wrong or shameful. No medical treatments are appropriate for children before they have reached puberty.

Adolescents once puberty has started

Assessment, information and support is provided to adolescents and families. For some young people it may be appropriate to consider medical treatments to manage their gender dysphoria which are commonly referred to as stage one and two.

Stage 1: Puberty suppression

Paediatric endocrinologists manage this stage of medical care. It involves taking medications to pause puberty, specifically, the development of secondary sex characteristics in adolescents such as chest growth or voice breaking.

Stage 2: Gender-affirming hormone treatment (or cross hormone treatment)

Paediatric endocrinologists manage this stage of medical care. This stage of medical care involves the use of medications such as oestrogen or testosterone that support changes in the body to align the person’s gender identity with their appearance. Gender affirming hormones help the young person look and feel like their identified gender with changes such as softer skin, changing body shape and the development of a chest.

References

Telfer, M.M., Tollit, M.A., Pace, C.C., & Pang, K.C. Australian Standards of Care and Treatment Guidelines for Trans and Gender Diverse Children and Adolescents, Medical Journal of Australian 2018; 209 (3)

WPATH (2011). Standards of care: For the health of transsexual, transgender and gender non-conforming people. 7th edition. World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

Vries, A. L., McGuire, J. K., Steensma, T. D., Wagenaar, E. C., Doreleijers, T. A., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2014, September 01). Young Adult Psychological Outcome After Puberty Suppression and Gender Reassignment. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2014/09/02/peds.2013-2958.

Developed by the Gender Clinic, Queensland Children’s Hospital. We acknowledge the input of consumers and carers.

Resource ID: FS235. Reviewed: August 2019.

Disclaimer: This information has been produced by healthcare professionals as a guideline only and is intended to support, not replace, discussion with your child’s doctor or healthcare professionals. Information is updated regularly, so please check you are referring to the most recent version. Seek medical advice, as appropriate, for concerns regarding your child’s health.