Pulmonary stenosis is a type of heart valve disease that involves the narrowing of the pulmonary valve, which controls the flow of blood from the heart's right ventricle into the pulmonary artery and to the lungs.

The condition is usually the result of the pulmonary valve not developing properly while a baby is growing in the womb. The cause of this is unclear but the condition accounts for about 10% of all congenital heart disease cases. Pulmonary stenosis may be associated with other cardiac abnormalities or syndromes, (e.g., Noonan’s syndrome) or develop later in life from complications of other illnesses including rheumatic fever.

There are four different types of pulmonary stenosis:

1. Valvar pulmonary stenosis

- A valve that has partially fused leaflets

- A valve that has thickened leaflets that do not open all the way

2. Supra valvar pulmonary stenosis

- A valve that is too small (hypoplastic)

- The main pulmonary artery just above the pulmonary valve is narrowed

3. Sub valvar (infundibular) pulmonary stenosis

- The muscle under the valve area is thickened, narrowing the outflow tract from the right ventricle

4. Branch/peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis

- The right or left pulmonary artery is narrowed, or both may be narrowed

Pulmonary valve stenosis ranges from mild to severe. Some people with mild pulmonary valve stenosis don't have any symptoms and may need only occasional health check-ups. Moderate and severe pulmonary valve stenosis may need a procedure to repair or replace the valve.

Signs and symptoms

Pulmonary valve stenosis symptoms depend on how much the blood flow is blocked. Some people with mild pulmonary stenosis do not have symptoms. Those with more severe pulmonary stenosis may first notice symptoms while exercising.

Signs and symptoms may include:

- A whooshing sound called a heart murmur (heard with a stethoscope)

- Being very tired and not keeping up with other children

- Poor weight gain

- Heart palpitations (sense of a rapid or irregular heartbeat)

- Shortness of breath, especially during activity

- Chest pain

- Fainting

- Babies may have blue or grey skin due to low oxygen levels.

Diagnosis

Pulmonary stenosis is often diagnosed via a test called a fetal echocardiogram when a baby is still in the womb. A fetal echocardiogram (also called a fetal echo) uses sound waves to create pictures of an unborn baby's heart.

The condition may also be detected after birth if a doctor hears a ‘murmur’ when listening to a baby’s heartbeat. A murmur is the noise heard when blood becomes turbulent when it travels through an obstructed area.

A cardiologist may order a series of tests including:

- an electrocardiogram (ECG), which measures the electrical activity of the heart.

- An echocardiogram

- Cardiac catheterisation – to measure pressures and oxygen levels in the heart and create images of heart structures using X-ray equipment.

Treatment

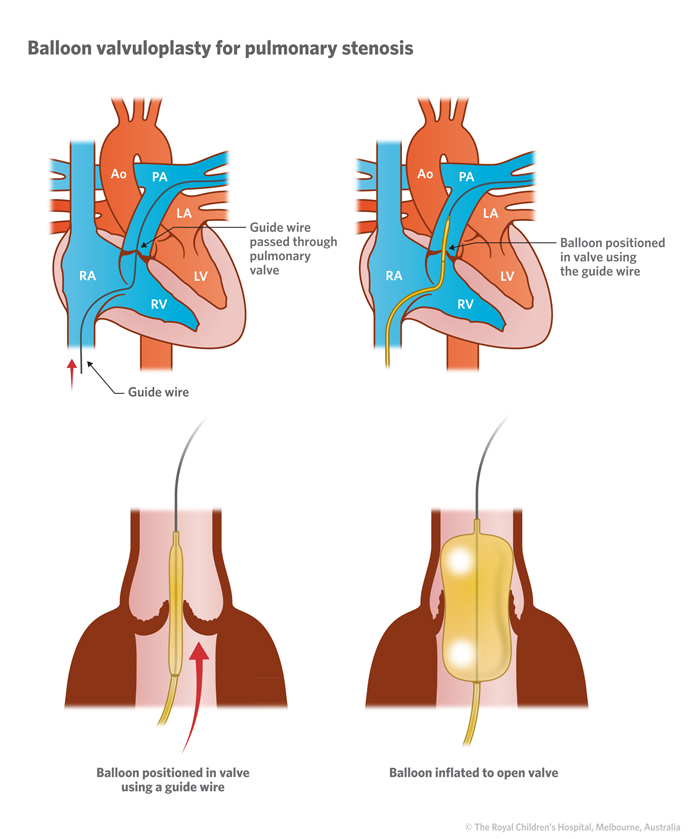

Treatment for pulmonary stenosis depends on a child’s age, overall health, and degree of stenosis. It can often treated with a procedure called a balloon valvuloplasty, in which a balloon is inflated inside the valve to stretch it. In cases of severe pulmonary stenosis, surgery may be required to repair or replace the valve.

Balloon valvuloplasty

This is performed via a procedure known as cardiac catheterisation. A flexible tube with an inflatable balloon at the tip is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin and passed up into the heart. When the tip of the catheter is through the pulmonary valve, the balloon is inflated to stretch open the valve. This usually produces effective long-term relief of the obstruction.

If a balloon valvuloplasty is unsuccessful or if a child is unsuitable for the procedure, surgery may be necessary.

Surgical repair

There are a number of surgery options for pulmonary stenosis. If the obstruction is due to thickened muscle tissue below the pulmonary valve (subvalvular stenosis), this tissue can be removed to widen the outflow tract.

If the valve itself is the problem, it may require surgery on the leaflets or it may be widened by the placement of a patch made of human tissue that has been cold stored.

A patch may also be inserted if the narrowing is above the valve (supravalvular stenosis) In all cases care is taken to preserve the pulmonary valve and ensure its proper functioning.

If a valve is unable to be repaired, it may need to be replaced with a donor human or animal valve.

Pulmonary stenosis can be a lifelong condition. A child will need to see a cardiologist regularly to check on at the functioning of the pulmonary valve. Children and teens who have moderate to severe pulmonary stenosis need to talk with their cardiologist about their activity levels and sport.

When to seek help

Call Triple Zero (000) and ask for an ambulance if your child:

- is short of breath at rest or with minimal activity, e.g., walking on a flat surface, cannot speak in sentences without becoming breathless.

- has chest pain – may feel like heaviness or someone sitting on their chest. May or may not radiate down arms or through to their back.

- Is fainting/losing consciousness or unable to sit up/stand without being dizzy or lightheaded.

- Looks pale or has blue lips, skin or nails.

Fast diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary valve stenosis can help reduce the risk of complications, including infective endocarditis , irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias), thickening of the heart muscle walls (hypertrophy), and heart failure.

If it’s not an emergency but you have any concerns or questions, contact yourGP or 13 Health (13 43 2584). If your child is under the care of a cardiologist, contact their cardiac care coordinator.

Developed by the Cardiology Department, Queensland Children’s Hospital. We acknowledge the input of consumers and carers. Illustrations courtesy of the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

Resource ID: FS373. Reviewed: July 2023.

Disclaimer: This information has been produced by healthcare professionals as a guideline only and is intended to support, not replace, discussion with your child’s doctor or healthcare professionals. Information is updated regularly, so please check you are referring to the most recent version. Seek medical advice, as appropriate, for concerns regarding your child’s health.

Illustrations republished with permission from The Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia. Images subject to copyright.