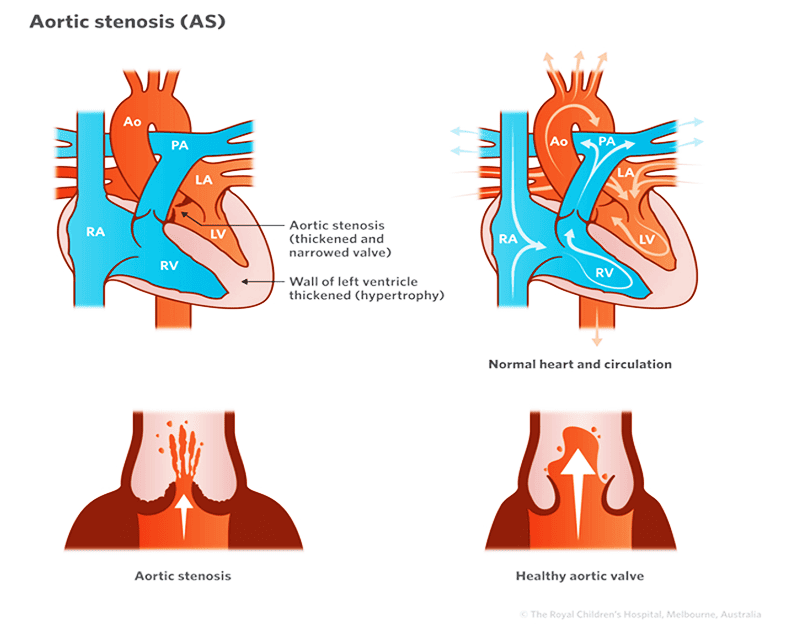

Aortic stenosis – or aortic valve stenosis – is a condition where the aortic valve in the heart is unable to completely open, which restricts blood flow from the left ventricle to the aorta. This restriction leads to the development of abnormally high pressure in the left ventricle as the ventricle must “push harder” to force blood through the narrowed valve.

The more severe the stenosis, the harder the left ventricle must work to pump blood to the body. If the problem is not treated, this overwork causes the left ventricle wall to thicken or “hypertrophy”. Eventually the muscle may become damaged, resulting in left-sided heart failure and abnormal heart rhythms.

Abnormal aortic valves may also fail to close properly, allowing blood to “leak” or flow back into the left ventricle; this is called aortic incompetence or regurgitation.

Aortic stenosis also increases the risk of developing infective endocarditis an infection in the lining of the heart.

Signs and symptoms

Mild aortic stenosis may cause no symptoms, but problems can occur when aortic stenosis is moderate to severe.

The main signs and symptoms include:

- Irregular heart sound (heart murmur)

- Shortness of breath during exercise

- Decrease in exercise tolerance (fatigue)

Diagnosis

Tests that help diagnose aortic stenosis include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) – measures the electrical activity of the heart.

- Echocardiogram (Echo) – uses sound waves to produce a picture of the heart.

- Cardiac catheterisation – A thin, flexible tube (called a catheter) in inserted into a blood vessel in the groin and fed up into the heart to measure pressures and oxygen levels, and visualise heart structures using X-ray equipment. The procedure is performed under a general anaesthetic. Learn more about cardiac catheterisation.

These tests are usually performed because a doctor has heard a heart murmur (turbulent blood flow) when examining a child with a stethoscope.

Treatment

Treatment for AS depends on a child’s age, overall health, and degree of stenosis. Mild aortic stenosis may not require treatment but more moderate to severe cases usually require treatment. This can be through a procedure called a balloon valvuloplasty, in which a balloon is inflated inside the valve to stretch it, or surgery to repair or replace the obstructed valve.

Balloon valvuloplasty

This is performed via a procedure known as cardiac catheterisation. A flexible tube with an inflatable balloon at the tip is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin and passed up into the heart. When the tip of the catheter is through the valve, the balloon is inflated to stretch open the valve. This can provide effective long-term relief of the obstruction.

If a balloon valvuloplasty is unsuccessful or if a child is unsuitable for the procedure, surgery may be necessary.

Aortic valve surgery

There are a number of surgical options including:

- Valvotomy is a procedure where the thickened and fused leaflets are surgically opened allowing the valve to function more normally.

- Aortic valve replacement is when the valve is replaced with either a human, animal, or artificial valve.

- Aortic homograft is when the valve and some of the aorta are replaced using a valve from a human donor.

- Pulmonary homograft (Ross Procedure) involves taking a section of your child’s own pulmonary artery including the intact pulmonary valve and using it to replace a section of the aorta and the aortic valve. The child’s pulmonary artery and valve is then replaced by using a valve and tissue from a human/cow/pig donor.

- Mechanical valves can also be placed in children. Blood thinning medications will be required long-term with this option.

When to seek help

Call Triple Zero (000) and ask for an ambulance if your child:

- is short of breath at rest or with minimal activity, e.g., walking on a flat surface, cannot speak in sentences without becoming breathless.

- has chest pain – may feel like heaviness or someone sitting on their chest. May or may not radiate down arms or through to their back.

- Is fainting/losing consciousness or unable to sit up/stand without being dizzy or lightheaded.

- Looks pale or has blue lips, skin or nails.

If it’s not an emergency but you have any concerns or questions, contact your GP or 13 Health (13 43 2584). If your child is under the care of a cardiologist, contact their cardiac care coordinator.