Management

Refer to flowchart [PDF 370 KB] for a summary of the emergency management of children with an acute allergic reaction.

Alert

Some insect bites or stings can result in severe abdominal pain and vomiting. This represents a severe allergic reaction and should be managed as for anaphylaxis.

Anaphylaxis is often under-diagnosed due to the variable nature and duration of symptoms.

Given the potential for rapid deterioration administer Adrenaline IM immediately into the thigh if anaphylaxis is suspected.

Anaphylaxis

Initial management includes rapid triage and clinical assessment of the patient’s airway patency, breathing (ventilation and oxygenation) and circulation. Intervention and stabilisation should occur immediately. Continuous cardiac and oxygen saturation monitoring is recommended. Children with less severe generalised allergic symptoms may initially appear stable but have the potential for rapid deterioration.9

Adrenaline

- Adrenaline IM into the thigh is the recommended first-line treatment of anaphylaxis

- effective for all the symptoms and signs of anaphylaxis2

- associated with a decreased fatality rate if administered promptly10

Studies have demonstrated that peak plasma levels are achieved significantly faster after IM injection into the thigh compared with SC injection into the arm.11,12 1 in 10 patients will need more than one dose of adrenaline.19

Nebulised Adrenaline may help relieve upper airway obstruction and/or bronchospasm but should only be administered in addition to Adrenaline IM.

Alert

Adrenaline IV should be reserved for the following children:

- immediately life-threatening profound shock

- circulatory compromise and continuing to deteriorate after Adrenaline IM

- refractory stridor or bronchospasm

- rebound of anaphylaxis despite recurrent more than 2 doses Adrenaline IM

Where Adrenaline IV is indicated, a continuous low dose Adrenaline infusion is the safest and most effective form of administration.13 Significant adverse events including fatal cardiac arrhythmia and cardiac infarction have been reported when Adrenaline IV is administered too rapidly, inadequately diluted or in excessive dose.14 An Adrenaline IV bolus can be considered for use in the hemodynamically unstable patient while preparing an adrenaline infusion.1 Staff with specialist training/most senior staff available will be required.

| Adrenaline dosing for the treatment of anaphylaxis in children |

|---|

See dose banding table below (Dose recommendations have changed) See skill sheet for drawing up Adrenaline in anaphylaxis |

| Adrenaline (IV infusion) | With Smart Pump Drug Errors Reducing System:

1 mL of 1:1000 Adrenaline solution (contains 1 mg) in 50 mL of Sodium Chloride 0.9%

Start infusion at 0.1 microgram/kg/min Without Smart Pump Drug Errors Reducing System:

1 mL of 1:1000 Adrenaline solution in (contains 1 mg) in 50 mL of Sodium Chloride 0.9%

Start infusion at 0.3 mL/kg/hour (0.1 microgram/kg/min) |

| Adrenaline (IV push dose) | 1 microgram/kg Take 1 mL of 1:10,000 adrenaline ampoule and make it up to 10 mL with 9 ml of sodium chloride 0.9% Final volume: 10 mL syringe: each 1 mL contains 10 micrograms of adrenaline (10 microgram/mL) Volume to administer: 0.1mL of this solution/kg see CREDD dosing See skill sheet for Adrenaline use in shock |

| IM Adrenaline dose banding (these doses are as per CREDD 2024) | |

|---|

| Indicative age | Dose and Volume of adrenaline 1:1,000 to administer |

| <10kg | 100 microgram (0.1 mL of 1:1,000) |

| 10-12kg | 100 microgram (0.1 mL of 1:1,000) |

| 13-15kg | 150 microgram (0.15 mL of 1:1,000) |

| 16-21kg | 200 microgram (0.2 mL of 1:1,000) |

| 22-34kg | 300 microgram (0.3 mL of 1:1,000) |

| 35-49kg | 400 microgram (0.4 mL of 1:1,000) |

| more than 50kg | 500 microgram (0.5 mL of 1:1,000) |

Seek urgent paediatric critical care advice (onsite or via Retrieval Services Queensland (RSQ)) for a child requiring more than two doses of Adrenaline IM or prior to administering Adrenaline IV.

Airway

- Children suffering from anaphylaxis who have respiratory distress without circulatory instability should be initially nursed in a sitting up position.

- Early preparation for advanced airway management

- For persistent stridor, consider nebulised adrenaline and continue to escalate anaphylaxis management Flowchart

Seek senior emergency/paediatric advice as per local practices for a child with airway concerns following administration of Adrenaline IM.

Contact the most senior resources available onsite (critical care/anaesthetic/ENT) prior to intubating a child with anaphylaxis.

Breathing

- high flow supplemental oxygen via non-rebreather mask is recommended

- for persistent wheeze, consider inhaled bronchodilators, magnesium, corticosteroids as per acute asthma management, in addition to escalating anaphylaxis management Flowchart

Circulation

- children with circulatory compromise should be nursed lying down

- elevate the lower extremities to conserve circulating volume

- IV access with two large-bore (age-appropriate) cannula, or intraosseous access, is recommended for children with severe symptoms at risk of circulatory compromise

- fluid resuscitation with sodium chloride 0.9% (in addition to IM adrenaline) for the management of shocked children

| Fluid resuscitation for the management of shocked children |

|---|

Bolus dose

(IV or IO)

|

Sodium Chloride 0.9% administered rapidly in 10 mL/kg bolus.

Repeat in 10 mL/kg boluses as clinically indicated.

|

- consideration of IV adrenaline infusion for refractory shock

- monitor for signs of overtreatment including pulmonary oedema and hypertension, with careful review and re-assessment of tachycardia, pallor and gastrointestinal symptoms

Seek urgent paediatric critical care advice (onsite or via RSQ) for a child in shock who is not responding to Adrenaline and fluids.'

Advanced Airway Management

Severe anaphylaxis is an incredibly challenging clinical scenario even for experienced clinicians. While most children respond well to IM adrenaline, airway swelling and bronchospasm can occur rapidly, with respiratory arrest being the cause of death in 86% fatal anaphylaxis cases.20

Preparation for early intubation with escalation to the most senior clinician available onsite is recommended if the child is desaturating. The airway should always be considered difficult, requiring smaller than usual endotracheal tube (ETT) size for age9. Caution should also be applied to Rapid Sequence Induction (RSI), requiring lower doses of sedation but maximising paralysis.

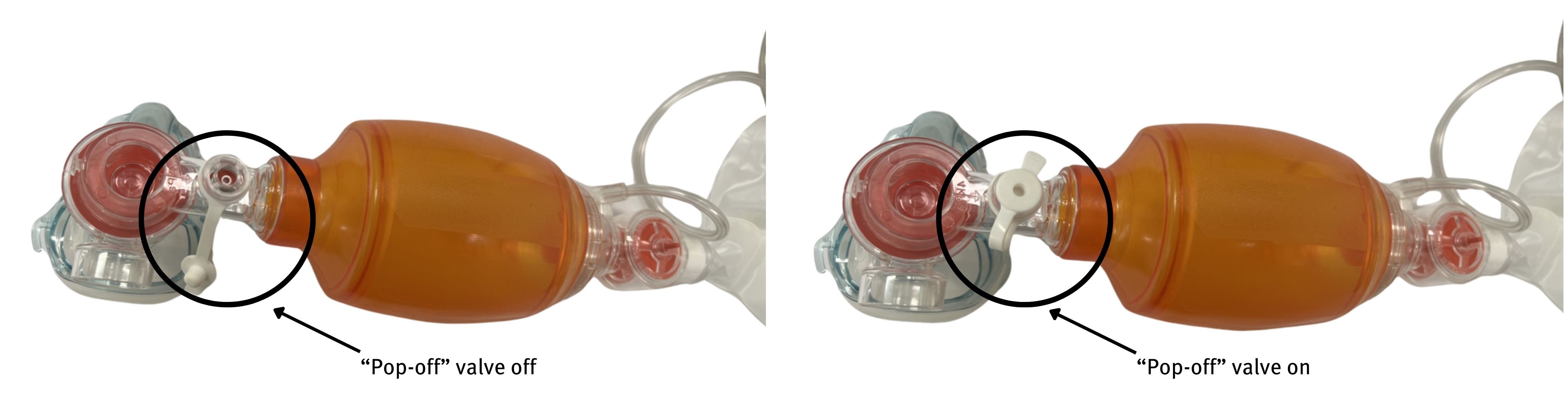

For the patient with progressive hypoxia or confusion despite maximum medical management, early intubation needs to be considered with anticipation of high airway pressure. When performing bag valve mask (BVM) ventilation, the pop off valve may need to be closed to achieve pressures required to overcome bronchospasm, while considering risk of inadvertent barotrauma.

Similarly, ventilation settings may need to be adjusted for peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) >50 and increased I:E, with consideration of pneumothorax in the case of secondary deterioration.

In the event intubation is unsuccessful, a clear escalation plan needs to be defined, with a surgical airway to be performed in the CICO situation.21

Profound and/or refractory anaphylaxis

Alert

Retrieval and admission to a paediatric critical care unit should be considered in any child with refractory anaphylaxis, any child with high risk or history of biphasic anaphylaxis, comorbidities such as asthma and for any patient with adrenaline infusion.

Anaphylactic shock displays features of both distributive and hypovolemic shock. If hypotension continues despite maximal adrenaline administration and large volume fluid resuscitation, additional therapies need to be considered and prepared22. These include additional vasopressors such as argipressin (vasopressin) (infusion via DERS software pumps at 0.01-0.12 unit/kg/h for < 20kg, 0.6-2.4unit/kg/hour for > 20kg) and methylene blue for profound vasodilatation (single dose 1 to 2 mg/kg by 20min infusion).

This should be discussed early with a senior physician in the paediatric intensive care unit or with the paediatric medical coordinator (PMC) via Retrieval Service Queensland (phone number 1300 799 127).

Adjuvant Therapy

Alert

IM adrenaline is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis. Additional therapies only to be used in conjunction with escalating anaphylaxis management.

Nebulised adrenaline

- nebulised Adrenaline may help relieve upper airway obstruction (stridor)

| Adrenaline (NEB) dosing for the treatment of upper airway obstruction | |

|---|

| Dose | 5 mL of undiluted 1:1000 Adrenaline nebulised with oxygen as a single dose. Dose may be repeated in 10 minutes if there is inadequate response(1) See skill sheet Adrenaline use in Stridor |

Inhaled bronchodilators

- may help relieve bronchospasm if lower airway obstruction (wheeze) is a concern18

| Inhaled Salbutamol dosing to aide in the treatment of anaphylaxis in children | |

|---|

| Metered dose inhaler (MDI)* 100 micrograms (spacer recommended) | Age 1-5 years: 6 puffs Age 6 years or more: 12 puffs |

| Nebulised | Age 1-5 years: 2.5 mg Age 6 years or more: 5 mg |

| Continuous nebulised Salbutamol | Neat Salbutamol nebuliser solution (5 mg/mL), replenish where reservoir empty. Use 5 mg/1 mL nebules or 30 mL multi-use bottle. |

Corticosteroids

- not recommended unless there is a component of asthma aggravation with anaphylaxis, which should be treated concurrently as per the Asthma Guideline.

Corticosteroid dosing for the treatment of asthma exacerbations in anaphylaxis in children | |

|---|

| Prednisolone (oral) | Day 1: 2 mg/kg (maximum 50 mg) Day 2 and 3: 1 mg/kg |

| Dexamethasone (oral/IM/IV) | Single dose on day 1 of 0.6mg/kg (maximum 16mg)1 Dexamethasone 0.5mg and 4mg tablets are available but they are not easily dispersed in water to give in a partial dose. Doses that can be rounded to full tablet size can however be crushed and dispersed in water.28 Dexamethasone injection can be given orally and is tasteless. If IV stock is in shortage, please give liquid suspension. |

| Hydrocortisone (IV) | 4 mg/kg (maximum 100 mg) then every six hours on day one |

OR Methylprednisolone (IV) | 1 mg/kg (maximum 60 mg) then every six hours on day one |

While corticosteroids are commonly recommended as second-line treatment internationally, little evidence supports their use in anaphylaxis. No randomised controlled trials (in adults or children) were identified in a Cochrane Systematic Review of glucocorticoids for the treatment of anaphylaxis.15 The primary action of glucocorticoids is down-regulation of the late-phase eosinophilic inflammatory response, as opposed to the early-phase response. Short-term glucocorticoid treatment is seldom associated with adverse effects.16 The proposed rationale for corticosteroid administration is to prevent biphasic or protracted reactions.2 However, in two paediatric studies of biphasic reactions the administration of steroids did not appear to be preventative.2

Antihistamines

- not recommended in acute anaphylaxis as there is no evidence to support use17

Generalised and local allergic reaction

Antihistamines

- H1 antagonists are recommended to treat allergy symptoms including urticaria, angioedema and itchiness

- two-to-four-day-course taken orally is recommended to alleviate persistent symptoms after a severe allergic reaction

Alert

Sedating antihistamines including promethazine (Phenergan) or dexchlorpheniramine maleate (Polaramine) are NOT recommended as may cause significant side effects such as respiratory depression, especially in younger children.

Antihistamine dosing for the treatment of allergic reaction in children

| Antihistamine | Age | Dose |

|---|

Cetirizine (Oral)

(Zyrtec)

|

1-2 years

|

2.5 mg twice daily

|

|

2-6 years

|

5 mg once daily or 2.5 mg twice daily

|

|

6-12 years

|

10 mg once daily or 5 mg twice daily

|

|

12-18 years

|

10 mg once daily

|

*Loratadine, Fexofenadine and Desloratadine are not available within QH Hospitals but are available in the community. Fexofenadine and Desloratadine can be prescribed to infants 6 months and over.